Dr Nicola Rivers and Dr Dave Webster.

In our recent work, looking at discourses of ‘resilience’ and ‘grit’ in Higher Education, we have made only passing reference to a phenomenon that seems to occupy much of the same narrative space, namely motivation porn. The term ‘motivation porn’ refers to a form of narrative that seeks to associate success with perseverance, and digging deep, telling the inspiring story of the student who overcame an array of difficulties, and then, despite it all, received a First-Class Degree. Of course, we are not against celebrating success, and there is often much to celebrate in the achievements of our students, but these stories should not be used in the service of shaming fellow students who haven’t managed to ‘beat the odds’ or promoting the idea that individualised understandings of resilience can substitute for collective support or systemic change.

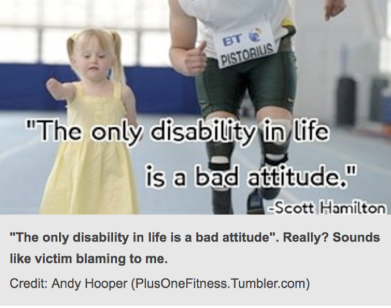

Our use of the term, motivation porn owes much to the more specific development of the term ‘inspiration porn’, coined by disability activists and those seeking to challenge ableism across society. The term has been around since at least 2012, when Stella Young, a disability rights activist wrote an ABC Australia piece, proclaiming:

Inspiration porn is an image of a person with a disability, often a kid, doing something completely ordinary – like playing, or talking, or running, or drawing a picture, or hitting a tennis ball – carrying a caption like “your excuse is invalid” or “before you quit, try”.

This captures the idea well. It is part of a cloying world of ‘positivity conquers all’. Only it doesn’t. Furthermore, the real barriers that disabled people face are often much more external than their attitude. As Stella Young notes:

Inspiration porn shames people with disabilities. It says that if we fail to be happy, to smile and to live lives that make those around us feel good, it’s because we’re not trying hard enough. Our attitude is just not positive enough. It’s our fault. Not to mention what it means for people whose disabilities are not visible, like people with chronic or mental illness, who often battle the assumption that it’s all about attitude. And we’re not allowed to be angry and upset, because then we’d be “bad” disabled people. We wouldn’t be doing our very best to “overcome” our disabilities.

Since 2012, inspiration porn has become much more common, with the adverts in the 2015 Super Bowl causing a backlash from disabled tweeters. And it is this quotation that most clearly highlights our concerns with the corresponding idea of motivation porn, and its conceptual cousin, perseverance porn. What is at work here, in these seemingly feel-good representations, is the notion that the difference between caving in to circumstances, and ‘transcending them’ is in our hands. It is a matter of being positive enough. Of trying hard enough. Familiar?

When we use motivation porn, we do so with a wide frame of reference – referring not only to disability, but also in our case, to students (and increasingly so-called Early Career Researchers), in poverty, with low cultural-capital, with caring responsibilities, specific learning needs, who are homeless, precariously employed, or vulnerable in a range of ways. Motivation porn then attempts to reframe circumstances that are for many, understandably insurmountable, as mere hurdles that those with enough personal resilience can scale. This might take the form of an academic who retells the tale, of a student who was homeless, and in crisis, but let them use the sports club showers, and gave them refectory vouchers, and after all the help – they made it! It is the story that makes the viewer feel a sense of gratification; gives them a warm glow. It is a form of pornography. As actual pornography, in most instances, is not hugely representative of most lived-experiences of sex, it is not the real world of most, or even many, students. When many of us hear these stories, we want to cry what about all your other students? Or Why did you need to bend over backwards to enable a student in hardship to access your provision – what about a better model of inclusivity that anticipates needs that students have?

As you might imagine, such discourses can be often found blended with middle-class saviour ideas (you had an actual working-class person on the course, and made it possible for them to pass? Well done you! Maybe, in half-term, a single-parent mother was given permission by you to bring her child to a class. Well done!), or ‘white-saviour’ accounts. What might be becoming clear here is that these narratives may celebrate the success of the individuals involved – whether that be the student who overcame adversity, or the lecturer who went the extra mile – but they also mark out students in need of help as exceptions, and those who are prepared to offer this help as exceptional. This exceptionalism has numerous features that cause us to flag it as a concern here.

These stories act to obscure, or eclipse, concerns about finance, childcare, support, illness, and disability that may affect a substantial proportion of students, or indeed academic staff. Systemic transformation that supports students needs to be modelled on an inclusivity principle that recognises the diverse and complex needs of all students. Such inclusivity is a not a reactive response to the exception, but anticipatory and recognises that classrooms, lecture halls and seminars groups are populated by people who may also be carers, parents, working two jobs, dealing with a range of health issues, and that many of these circumstances will not be visible or known to the tutors and institutions.

As many writing about inspiration porn in the disability context have noted, it can also run the risk of constituting a form of victim shaming. Did those who didn’t overcome their barriers get a mention? Maybe they didn’t have enough grit, or weren’t resilient enough. These stories, in their telling may or may not make explicit reference to the character traits that let their subject succeed, but a meritocratic narrative, of the brave, tough, determined overcomer, lurks near the surface of the discourse.

We might end with two reflections. One concerns why we seem to find these motivation tales so compelling in the sector. Partly this is because our wider society is also rife with them, and they allow us a warm sense of satisfaction, and virtue. Like the various awards for those who have volunteered with charities, we don’t ask why we need volunteer heroes to transform the lives of those in need, or why they are in need anyway, we are merely encouraged to be passive recipients of a gratification-delivering narrative. We do want education to transform lives, but this exceptionalism, though it may make us feel lovely, is misleading and dangerous, especially for those already marginalised or vulnerable. In short, because if they aren’t inspirational enough, or just need unglamorous support – in large numbers – they don’t fit the story.

Secondly – what can we do about it? Probably stop doing it. Despite the temptation at Open Days, on blogs, at events where we want to all congratulate ourselves; we need to think what would we need to do, to allow us to tell better stories? For example, creating an assessment regime that allows alternative methods of presentation, if requested, fails to anticipate diversity of experience or needs as the norm. Better practice then would be to have the primary assessment as it is presented to students, have flexibility built into it for all students, not just those who are identified as unable to complete the normal mode of assessment. These stories might have to have some data, about, say, how we reduced waiting times to see a counsellor for students with anxiety, or increased the use of truly inclusive (rather than reactive) assessment strategies, or used digitisation on more course materials to reduce the costs, and access-barriers, to students accessing our provision. These stories might not make us feel good in the same way. But making them true might actually do more good.

Systemic, inclusive support is harder to turn into a meme, gets less likes, and we may tear-up less when recounting it at a dinner-speech event, but ultimately is better for, and this is the point, everyone.

The content reminds me of the work of Alfie Cohn and his book Punished By Rewards – a great read.

I like the intersectionality of disability, race and other traditionally porned/pitied and charitied groups. For the best of Queen For A Day, 2017 see the NYT Neediest Cases column – it is especially good around the holidays!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A former student and I wrote about this ‘Hollywood hero’ narrative in our criticism of mental toughness rhetoric in sports. The idea that success will come to those who have enough mental toughness (whatever that is). We pointed out that mental toughness is only ascribed after the event, i.e. those that are successful are labelled as mentally tough, whilst those that fail and give up are labelled mentally weak. This whole rhetoric can be insidious and lead to incredibly damaged athletes, i.e. those that suffer long term injury because they pushed themselves through the pain barrier to achieve athletic success.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Better practice then would be to have the primary assessment as it is presented to students, have flexibility built into it for all students, not just those who are identified as unable to complete the normal mode of assessment.” This is at the heart of inclusion, not just in education or research but across the board. Inclusive environments benefit everyone. Where the difficulty arises is when different access needs conflict. Still recall a disability conference where clapping produced sensory overload for autistic delegates so waving was used instead. This left a visually impaired presenter uncertain at the end of her very brilliant presentation because she couldn’t ‘see’ the applause. And I know this is specifically about education, but the ‘what to do?’ needs to aim higher and look at meaningful social change.

PS: On the subject of awards, I was made Student of the Year, not for being the only person in my year to get first, but because I had ‘overcome significant personal and emotional difficulties’. So yeah, thanks for outting me to everyone in the ceremony as having mental ill health.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Projects of the Self.

LikeLike

This is so important!! I am a physics student from many marginalized communities. The only time i see women being talked about naturally is when past physicist have won the noble prices or discovered things and how their rightful price was stolen from them. When the only time issues causing harm to the entirety of the community are talked about when and if someone ‘makes it’ and ‘fights’…it is hard for the people to not think that they absolutely have to do the so and so impossible accomplishment to belong.

When i was little i used to scream i would be a physicist and win the noble price. Now i cry about it. I have grown up with this demand of sorts from within that if i am in stem and not a man, i need to do something life changing and remarkable. Dreams become obsessions if the dreamers find themselves purposefully alienated and only seen when they win, which often comes at the cost of dying.

Really great and necessary article! Nice to know that i am not the only one 🙂

LikeLike