Does anyone need to remember or know anything anymore? We carry the sum of all human knowledge in our pocket, so can’t we just look stuff up? But this atomised attitude towards knowledge as mere lists of discrete facts is hugely inadequate.

Not only is there the matter of knowing what to ask, but most of us recognise that we cannot evaluate the compelling and competing claims of the internet, or any purveyor of apparent answers, without substantial contextual awareness. There is an underlying philosophical problem here which is that we don’t know in advance what is likely to be relevant or have a bearing on a topic in advance.

This is part of the suite of epistemological issues raised by the ‘the frame problem’ in AI. How can AI systems discern which data is pertinent without considering all apparently irrelevant data? Which data will pertain to which topics in a reliable and meaningful way? Of course in the large-language models (LLM) that have dominated the Generative AI (GAI) fields (and news agenda), the tools just see what has been deemed relevant in the source materials the systems have been trained on. What is judged as relevant now is what has been adjudged to be relevant previously. If we rely on GAI to create answers to our questions, these answers will be shades and remixes of what has been thought to be the answer before. These tools might be generative, but they are not intuitive and creative.

If we wanted to address this changing how the GAI systems work, we could here be distracted by thinking about whether underlying AI models need a level of informational unencapsulation which is not present in the apparent modularity of some human cognitive processes. There are problems with such an approach, because there are good reasons for the cognitive encapsulation we see in the human mind: if one area ‘misfires’, the whole system is not overwhelmed by this error (the common example is of a basic optical illusion. While it ‘fools’ part of the mind – the error stays there as other ‘unimpacted’ parts of the mind are sufficiently modular and separate and therefore able to see the error for what it is. In AI systems without the lived experience (or ‘common sense-experience’ we might call it) in which to ground judgements in, maybe they need all the encapsulation they can get, to prevent small errors becoming system-wide immediately.

If then the issue of epistemological pertinence isn’t best addressed by the ‘how’ of the Ai system, the other approach is through the training materials – the data the GAI system remixes and shuffles to generate its outputs. To avoid answers from GAI systems calcifying around existing content, a constant stream of new data, of creative thinking and writing by humans, that makes hitherto unseen connections between otherwise seemingly unrelated conceptual content is vital.

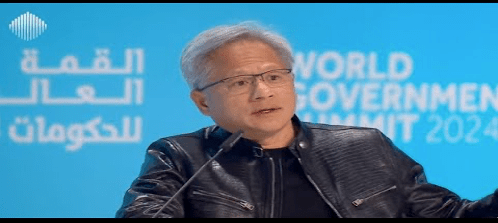

These thoughts were in my mind when I watched this interview with Jensen Huang (founder of NVIDIA). Asked, at a 2024 World Government Summit in UAE, what the focus should be for education in an AI age – how should we educate our kids and societies? Jensen answers by stating that his answer is going to differ from those people who sit on such stages usually give. He says he isn’t advising the study of computer science, or that everyone should learn to code. Now we have the wonders that AI offers in terms of assisting us to solve problems – the people who are going to be able to formulate the problems and work with AI to solve them are those with what he calls ‘domain expertise’. He cites expertise in digital biology, manufacturing, education, and in farming. It made me reflect on the points I began with – to make the most of the opportunities of GAI we need to know our stuff. We need to be experts, or emerging as such and engage meaningfully with the issues in our fields of study and only then can we see creative approaches, new possible connections and use the staggering computational and algorithmic grunt of GAI systems to test, develop and realise our ideas.

When the chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov was defeated by IBM’s Deep Blue in 1997 (as I was reminded by IBM’s Jez Bassinder in a recent talk) his subsequent position was clear and one he repeated on several occasions. He sees that huamns working with technology will outperform either humans alone or technology alone. In a 2018 interview he said:

With so much power now brought by machines, we have to find a refuge in our humanity. It’s about our creativity, our intuition, our human qualities that machines will always lack. So we have to define the territory where machines should concentrate their efforts. This is a new form of collaboration where we recognize what we’re good at and not interfere with machines where they’re superior—even if it hurts our pride.*

As a scholar with a humanities background, and as an advocate for Higher Education, it is refreshing and instructive to focus on Huang’s point: the expertise matters. Superficial engagement with GAI systems will tell us things that are already known, or widely believed, if not by us as individuals. GAI in the hands of genuine experts, with specific disciplinary depth combined with the breadth of human experience and ideally a solid educational basis in a range of areas – this could be another thing altogether! This is where we might start to amaze even ourselves with what we can achieve, but we cannot do it without experts and expertise.

*Cited in a Medium article at https://medium.com/@Jordan.Teicher/garry-kasparov-its-time-for-humans-and-machines-to-work-together-8cd9e1dc735a

Leave a comment