The context for this set of reflections is the ‘Trad Vs Prog’ debate, which rages amongst teachers of school-age children, but also has substantial importance for HE educators. While on Twitter the debate is often fierce and contains more heat than light, there are important, deeply political (what is education even for?), high-stakes (whether certain approaches actually help students and the world) matters at hand. Many style the direct-instruction model, beloved of the traditional approach, as being research informed, while the student-led interactive progressive approach is often then cast as faddish. Pieces such as the influential Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching, by Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark* argue that ‘human cognitive architecture’ is such that direct instruction is preferable as a mode of teaching that generates effective learning. The approach taken in this piece is strident, and in its closing paragraph the authors assert:

It is regrettable that current constructivist views have become ideological and often epistemologically opposed to the presentation and explanation of knowledge**.

It is with a recent re-read of this in my mind, that I travelled to witness the use of a learning model that seemed like just the kind of thing the Direct Instruction/Trad advocates dispute the efficacy of.

Last week as a SOAS member of staff. I had the privilege of visiting the African Leadership University (ALU), at their Rwanda campus. SOAS have a partnership with ALU, and there are various aspects to this, and I was there to try and take a variety of these forward, but a key interest of mine was around their innovative pedagogic work, and how their model operates, particularly in light of the concerns above.

ALU have a very specific goal, and make both this, and the approach they take to achieving it, clear on all of their materials – where it states:

ALU aims to develop 3 million ethical and entrepreneurial leaders for Africa and the world by 2035. It uses a personalized, student-driven, project-based, and mission-oriented approach to create agile, lifelong learners who can adapt to a changing world.

This student-driven and project-based approach had been praised by colleagues I respect, and I was excited to see it in practice. I’d been warned that there were no observers in the class, so I’d better be prepared to participate fully. It was with this anticipation in my mind, that I sat on Rwandair flight, whose in-flight choices seemed to include Elf, amongst more recent releases. The economy cabin was fairly quiet, and I stretched over nearby seats, and dreamt some slightly confused, festive, dreams as the night flight made its way to Kigali.

After arrival, I headed to my first, fairly informal as it was a Sunday, meeting. After some location errors on my part and frantic taxi activity, I met with ALU colleagues and planned out some of the week’s work. Then I went for a walk.

Well, Dr Sindi Gordon, of SOAS and Sussex, who had helped me plan the trip and is spending some months working at ALU, and furthering the partnership, and I decided not to get a taxi, but walk to the area I was staying in. We set off in the right direction, we thought, and started to chat. After 20 minutes, or so, I asked Sindi if this was the direction we needed. We’d neither been paying attention, I had no phone data coverage (the only way I navigate these days) and her phone was dead. So, we kept walking. And walking. Occasionally we caught sight of the Kigali Convention Centre (our approximate target), but it never got any closer. By now we were out on a dusty, not-quite-finished ringroad, and most people we asked were Kinyarwanda speakers. We were lost. Eventually we realised the direction we wanted was behind us. Across a valley. Later, looking at a map, I worked out our walk was over 7 miles long, in the afternoon sun. I obviously retained no useful information on the urban geography of Kigali, and only towards the end of my stay began to get an even vague sense of the relative layout of places that I visited 5 days in a row. Nonetheless, I did get a partial sense of Kigali on that long Sunday wander. The obvious contrast between the smart Western hotel we’d met at earlier and the poor parts of the city was not unexpected, but nonetheless disconcerting; but Kigali is also incredibly clean (the plastic bag ban surely helps this) and green.

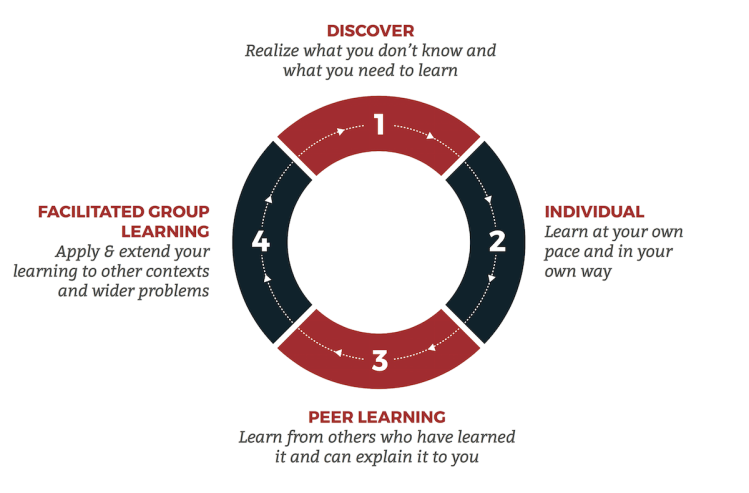

So, it was slightly weary legs, that I walked to ALU’s current Kigali Heights location to take part in two Monday morning classes. One about ‘designing educational interventions’, and another where students pitched their ‘communicating for impact’ (CI) projects to me in small groups. The CI work seemed like just the type of problem/inquiry-based work that Kirschner, Sweller & Clark’s direct instruction advocates are so hostile to. The students showed me the presentations they had designed for various ventures – gym clubs, healthy eating initiatives, and more. What became clear as they did so, was that although the face-to-face sessions with facilitators (which is what ALU calls its teaching staff) are largely student-led, they have learnt research methods, presentation styles, market analysis and the like. Much of this is via the VLE/LMS, which has support materials, though I am not sure whether this counts as direct or indirect instruction. What is also clear is that the activities are structured, and goal driven, and that this structure is provided in short, but well-attended-to, bursts of facilitator-led direct instruction. The model is still absolutely student-led, and project-based, but within this there are knowledge-rich online materials on VLE/LMS, with a level of care and skill in the facilitation process that interweaves the content-acquisition into segmented delivery sessions. This seems to me to be, as per the title of this piece, to preserve the project-based approach while retaining the expert-novice knowledge transfer, on an as-needed basis.

In a piece about the Trad-Prog debate in School Teaching, Tom Sherrington notes, citing the research of Robert Slavin on group work, that:

Informal group work, where students simply work together in a self-directed manner on a shared task is largely ineffective. However, where students are given clear roles and the tasks are carefully structured so that success in achieving the group goal relies on the combined success of each individual, studies do show strong gains. Good group work works! Sadly, Slavin’s research shows that the vast majority of the group work teachers tend to organise is of the ineffective informal variety. Clearly, we need to factor in the quality of what we do in any debate about ‘what works’.***

One of the key recommendations from Slavin’s study is that educators are clear about what they are trying to achieve with group activities. Further to this, Slavin talks of the benefits of ‘ structured team learning methods’, as opposed to informal group work. Both the Slavin study, and the Kirschner, Sweller & Clark article date from 2010, and it may be that there has been a shift in practice, but the sessions I observed at ALU were well-planned and structured activities.

This has a wider application, as I wonder how much the Trad critique of problem-based learning, et al, is based in a Straw Man fallacy, applicable only to poorly conceived and badly delivered problem-based learning. The lesson I take from these reflections is one I would also apply to lectures/direct-instruction delivery too. This is a lesson about clarity of purpose, structure, and what increasingly is best captured by the term ‘learning design’. The sessions I witnessed last week fulfilled all these. The students had clearly acquired new knowledge, as well as sharpening skills, (both technical and interpersonal). The ALU institutional clarity of purpose, aided by a culture shared by students and staff alike of determined optimism^, cascades down in a constructive alignment whereby ‘knowing why you are doing things’ is an institutional ethos. In this context, the blending I saw still has a right to call itself project-led, and inquiry-based, but in a manner that ensures that as students work, they are instructed, guided and ultimately, not unlike my city-wide wanderings but in a less circuitous manner, find their way.

—

* Paul A. Kirschner , John Sweller & Richard E. Clark (2006) Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching, Educational Psychologist, 41:2, 75-86, DOI: 10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1

**Ibid, p.84

*** Tom Sherrington. Is there a right way to teach? Making sense of the trad-prog debate. https://teacherhead.com/2018/05/27/is-there-a-right-way-to-teach-making-sense-of-the-trad-prog-debate/

^The location matters here. In Rwanda, there is a political commitment to the notion of optimism and the possibility of growth and development. This also manifests as a genuine pragmatism, and earnest seriousness about what works. I left the country as the memorial week, marking the 25th anniversary of the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, began. While clearly masking some complexity, nonetheless there is a narrative about the country that is powerful, and predominates amongst the, mostly, pan-African students that attend the site I visited. An element of this narrative is that education is too important to be cynical about. As a pedagogic utopian, I was genuinely awed and humbled by the common sense of endeavour.

Also see: Robert Slavin: Co-operative Learning: What Makes Group Work Work? http://www.curee.co.uk/files/publication/%5Bsite-timestamp%5D/Slavin%20%282010%29%20Cooperative%20learning.pdf